Wolf Call: Freedom or Security?

November 5, 2018

Would you prefer to be free as a wolf in the wild, free to roam, or secure on a dog-sled team, safe and well-fed, with purposeful work?

I came across this beautifully filmed short documentary called Vargsamtal, which means wolf call in Swedish. It’s about a dog sledder, Sven Engholm, working in the extreme north of Norway, far above the Arctic Circle. Engholm tells how a group of stray dogs joined his dogsled team on an expedition, and imagines what the howls exchanged between the harnessed dogs and the wild wolves nearby might have meant:

“We had crossed the Obi River where there were various fishing camps. Russian stray dogs were roaming around the camps. They seemed to be surviving on the leftovers from the fishing.

“The dogs began to follow our trail, some of them for several days. We felt bad about them leaving the camps, so my friend said, ‘Let’s give them a harness along with the others and see if they’ll pull the sled.’

“It went surprisingly well as they were big and healthy dogs, pretty similar to ours.

“At night we noticed three or four heads popping up behind the dunes…a wolf pack stalking us for several days.

“When we were freezing in the tent we could hear the wolves howl and the dogs answering back. It was like they were talking to each other, as if they were having a conversation, understanding each other.

“The wolves say: ‘You dogs are so dumb pulling that sled without purpose. We’re wolves and we can run free. We represent freedom and we do as we please.’

“The Russian stray dogs answer, ‘We also know what it’s like to be free: that means being hungry, getting hunted. That freedom of yours has a heavy price. We like this expedition. They give us food and shelter and we work from 9 to 5.’

“That’s how we imagined an argument between dogs and wolves.”

Freedom versus security is really a false choice, since we always want both and try to maintain a reasonable balance between them. But sometimes, one side may feel too extreme for comfort and the balance becomes skewed. When that happens, we feel the need to offset it.

Unwanted behavior like emotional eating is motivated by something, whether we’re aware of the motive or not. When the control that security or conformity requires begins to feel constraining, we may counterbalance it by acting in some way that goes against our normal preferences to emphasize our autonomy and restore equilibrium.

Often, the need to achieve psychological balance can be even more important than acting in our own best interest.

My book, 8 Keys to End Emotional Eating: Autonomy and the Spirit of Rebellion is forthcoming from W.W. Norton in the Summer of 2019. It’s available now for pre-order on Amazon.

New medical advances marking the end of a long reign for ‘diet wizards’

Insomnia Cured Here/Flickr.com, CC BY-SA

David Prologo, Emory University

For many years, the long-term success rates for those who attempt to lose excess body weight have hovered around 5-10 percent.

In what other disease condition would we accept these numbers and continue on with the same approach? How does this situation sustain itself?

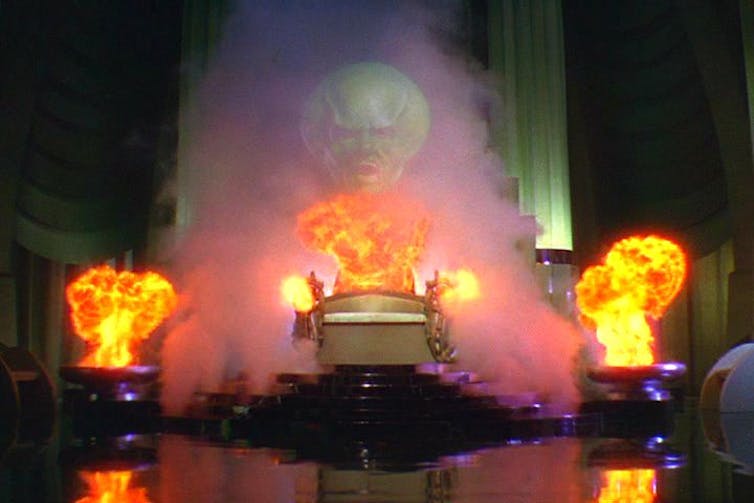

It goes on because the diet industry has generated marketing fodder that obscures scientific evidence, much as the Wizard of Oz hid the truth from Dorothy and her pals. There is a gap between what is true and what sells (remember the chocolate diet?). And, what sells more often dominates the message for consumers, much as the wizard’s sound and light production succeeded in misleading the truth-seekers in the Emerald City.

As a result, the public is often directed to attractive, short-cut weight loss options created for the purposes of making money, while scientists and doctors document facts that are steamrolled into the shadows.

We are living in a special time, though – the era of metabolic surgeries and bariatric procedures. As a result of these weight loss procedures, doctors have a much better understanding of the biological underpinnings responsible for the failure to lose weight. These discoveries will upend the current paradigms around weight loss, as soon as we figure out how to pull back the curtain.

As a dual board-certified, interventional obesity medicine specialist, I have witnessed the experience of successful weight loss over and over again – clinically, as part of interventional trials and in my personal life. The road to sustained transformation is not the same in 2018 as it was in 2008, 1998 or 1970. The medical community has identified the barriers to successful weight loss, and we can now address them.

The body fights back

For many years, the diet and fitness industry has supplied folks with an unlimited number of different weight loss programs – seemingly a new solution every month. Most of these programs, on paper, should indeed lead to weight loss. At the same time, the incidence of obesity continues to rise at alarming rates. Why? Because people cannot do the programs.

First, overweight and obese patients do not have the calorie-burning capacity to exercise their way to sustainable weight loss. What’s more, the same amount of exercise for an overweight patient is much harder than for those who do not have excess body weight. An obese patient simply cannot exercise enough to lose weight by burning calories.

Second, the body will not let us restrict calories to such a degree that long-term weight loss is realized. The body fights back with survival-based biological responses. When a person limits calories, the body slows baseline metabolism to offset the calorie restriction, because it interprets this situation as a threat to survival. If there is less to eat, we’d better conserve our fat and energy stores so we don’t die. At the same time, also in the name of survival, the body sends out surges of hunger hormones that induce food-seeking behavior – creating a real, measurable resistance to this perceived threat of starvation.

Third, the microbiota in our guts are different, such that “a calorie is a calorie” no longer holds true. Different gut microbiota pull different amounts of calories from the same food in different people. So, when our overweight or obese colleague claims that she is sure she could eat the same amount of food as her lean counterpart, and still gain weight – we should believe her.

Lots of shame, little understanding

Importantly, the lean population does not feel the same overwhelming urge to eat and quit exercising as obese patients do when exposed to the same weight loss programs, because they start at a different point.

Sheila Fitzgerald/Shutterstock.com

Over time, this situation has led to stigmatizing and prejudicial fat-shaming, based on lack of knowledge. Those who fat-shame most often have never felt the biological backlash present in overweight and obese folks, and so conclude that those who are unable to follow their programs fail because of some inherent weakness or difference, a classic setup for discrimination.

The truth is, the people failing these weight loss attempts fail because they face a formidable entry barrier related to their disadvantaged starting point. The only way an overweight or obese person can be successful with regard to sustainable weight loss, is to directly address the biological entry barrier which has turned so many back.

Removing the barrier

There are three ways to minimize the barrier. The objective is to attenuate the body’s response to new calorie restriction and/or exercise, and thereby even up the starting points.

First, surgeries and interventional procedures work for many obese patients. They help by minimizing the biological barrier that would otherwise obstruct patients who try to lose weight. These procedures alter the hormone levels and metabolism changes that make up the entry barrier. They lead to weight loss by directly addressing and changing the biological response responsible for historical failures. This is critical because it allows us to dispense with the antiquated “mind over matter” approach. These are not “willpower implantation” surgeries, they are metabolic surgeries.

Second, medications play a role. The FDA has approved five new drugs that target the body’s hormonal resistance. These medications work by directly attenuating the body’s survival response. Also, stopping medications often works to minimize the weight loss barrier. Common medications like antihistamines and antidepressants are often significant contributors to weight gain. Obesity medicine physicians can best advise you on which medications or combinations are contributing to weight gain, or inability to lose weight.

Third, increasing exercise capacity, or the maximum amount of exercise a person can sustain, works. Specifically, it changes the body so that the survival response is lessened. A person can increase capacity by attending to recovery, the time in between exercise bouts. Recovery interventions, such as food supplements and sleep, lead to increasing capacity and decreasing resistance from the body by reorganizing the biological signaling mechanisms – a process known as retrograde neuroplasticity.

Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity, CC BY-SA

Lee Kaplan, director of the Harvard Medical School’s Massachusetts Weight Center, captured this last point during a recent lecture by saying, “We need to stop thinking about the Twinkie diet and start thinking about physiology. Exercise alters food preferences toward healthy foods … and healthy muscle trains the fat to burn more calories.”

The bottom line is, obese and overweight patients are exceedingly unlikely to be successful with weight loss attempts that utilize mainstream diet and exercise products. These products are generated with the intent to sell, and the marketing efforts behind them are comparable to the well-known distractions generated by the Wizard of Oz. The reality is, the body fights against calorie restriction and new exercise. This resistance from the body can be lessened using medical procedures, by new medications or by increasing one’s exercise capacity to a critical point.

![]() Remember, do not start or stop medications on your own. Consult with your doctor first.

Remember, do not start or stop medications on your own. Consult with your doctor first.

David Prologo, Assistant Professor, Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences, Emory University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Dieting and the Minnesota Starvation Experiment

December 18, 2017

In the Winter of 1944, World War II was ending and there were horrific stories of widespread starvation across Europe. The American government would soon be responsible for a massive refeeding project overseas, but there were no medical guidelines for how this should be done. Ancel Keys, a professor of physiology at the University of Minnesota, had been involved at the start of the war in the development of field rations for the American military. Now he was asked to design a study that could provide data to guide the refeeding project. Thirty-six men volunteered to participate in a year-long study of starvation. These men were all conscientious objectors who were allowed to participate in human performance studies as an alternative to military service.

During the first three months of the study, each participant was fed a tightly controlled diet intended to standardize his weight to match the average for American men of his height. Most needed to gain a fair amount. After the three-month standardization phase, during which the volunteers’ three daily meals totaled about 3200 calories, the six-month starvation phase of the experiment began. In a single day, the men’s calorie allotment was cut approximately in half.

To put this in context, if an adult male today asks for guidance about going on a quick yet still safe way to lose weight without medical supervision, the recommendation would be to limit his daily intake to 1500 calories. That’s low but is still considered safe and nutritionally adequate. For a woman, that number would be 1200 calories a day. In contrast, to reproduce the effects of involuntary starvation, the average number of calories allowed in the Minnesota experiment was 1570 per day—more than many dieters would now be advised to eat on a non-medically supervised weight-loss regimen!

This made me wonder about the more restrictive dieters who I see in therapy. Although it’s considered a medically safe level of intake, what are the psychological consequences of such a diet? How might it affect adherence when meals aren’t being carefully controlled as they were in the experiment? After losing weight on such a diet does eating just return to normal? What are the long-term effects of this kind of self-deprivation on the body’s metabolism afterward?

In the starvation experiment, the psychological effects of the diet began quickly and soon became dramatic. After just a few weeks, volunteers who kept diaries began to describe how the time between meals had become difficult. One participant began to have nightmares about cannibalism—dreaming that he was the cannibal. This affected that volunteer’s adherence to the routine as well. In an effort to end these dreams, he began cheating on the diet. During their unsupervised free time, he began to leave the university campus where the experiment was being held, to go into the nearby town where he would buy milkshakes and ice cream. The cheating was quickly discovered because his expected weight loss had leveled off. But even after he was caught and his freedom to leave campus was taken away, he found other ways to cheat on the diet and he was soon released from the experiment.

Although this was the earliest psychological reaction among the participants, the others soon began to show signs of abnormal food preoccupation as well. One notable incident occurred when Dr. Keys, the director of the experiment, decided to offer a “relief” meal to the group in order to boost morale and hopefully prevent others from cheating. The calorie content of this meal was considerably more generous than the typical ration, and it included an orange for dessert. When the men finished eating and they were ready to return their trays, nothing was left but the silverware, plates, used napkins, and orange peels. As Todd Tucker described the scene in his book, The Great Starvation Experiment, “None of them could bring themselves to throw it away. The idea came to them collectively. They picked up the orange peel and ate it, every one of them.” Keep in mind that this was after a relief meal of 2,366 calories, after fifteen weeks at the starvation level. The impulse to eat orange peels was not borne of hunger, but psychological scarcity.

As the days wore on, there were more incidents of cheating. Another person was dropped from the experiment when, alone at his night job in a grocery store in town, he suddenly found himself binging on stale cookies and rotten bananas that he was about to throw into the dumpster. Another had to fight the urge to root through a trashcan full of decaying garbage while on his daily walk.

Although the purpose of the experiment was to learn how to safely refeed starving civilians, the volunteers’ stories also highlight important lessons about the effects of dieting on the mind and body. The key lesson is that even restricting food to a degree that might be considered reasonable for a normal weight-loss diet, can have profound psychological and behavioral effects. It’s worth taking that into account if you’re thinking about starting–or recommending–a diet.

My book, 8 Keys to End Emotional Eating: Autonomy and the Spirit of Rebellion is forthcoming from W.W. Norton in the Summer of 2019. It’s available now for pre-order on Amazon.

The Top 5 Excuses for Blowing Off Your Diet

January 23, 2017

When January comes to an end, New Year’s resolutions often do as well – especially if it’s a resolution to diet. Although you’re sincere in your commitment to lose weight, if you’re on a diet you may find that with each passing week, you’re increasingly likely to come up with reasons to make an exception. For many, that exception becomes the rule.

After years of doing psychotherapy with people who struggle with emotional eating, I’ve heard countless stories from my patients about their experiences on diets, and why those didn’t work. They usually can recall some incident that made them feel that they’ve just blown the diet, and they might as well give it up.

After hearing this theme repeated often enough, I’ve been able to identify the five most common explanations for why people decide to go off their diet. If some of them sound like lines you’ve used to explain your own behavior while dieting, then this list may be a useful reality check for you:

- “It was a special occasion so I felt it was okay to make an exception.”

Your intention is not to give up on your diet because that would make you feel like you failed. So instead, you only go off it on “special occasions,” and that doesn’t really count as cheating.

The reality is you want it both ways: to tell yourself that you’re still on a diet without having to follow it. The only way to do that is to set a very low bar for declaring a special occasion. When any opportunity can be considered special enough to go off your diet, the words ‘special’ and ‘diet’ lose all meaning.

2. “I feel down and bored and thought it would make me feel better to eat.”

Your intention is that when you’re feeling down, eating something that tastes delicious will make you happy. It’s as if comfort food can be like edible therapy.

The reality is that after eating it, you quickly realize that the food didn’t help and now you feel guilty, out of control, and in a much worse mood than you were in before. That’s because being on a diet may be a big part of why you feel depressed. It controls you, deprives you, and reminds you that you can’t be trusted to make good choices. When you decide to break the diet, it gives you a brief thrill of doing something “bad” which helps you feel back in control, until the regret sets in.

3. “I’m restarting my diet tomorrow so I’ll never eat this again.”

Your intention is that this is just a temporary, one-time detour from your commitment to lose weight, so what’s the harm? After this, you’ll commit to the diet again and you’ll stay on it.

The reality is that your body doesn’t care when you resume the diet, so there’s no difference between starting tomorrow or next Monday or right now. The real reason you want to postpone restarting your diet is because once you’re back on it, you believe that you’ll stick with it. Until then, you have this window of opportunity for one last all-you-can-eat buffet.

4. “I’ve already ruined my diet by having that cookie, so it makes no difference what I eat now.”

Your intention is to be brutally honest about your behavior, so you tell yourself that you’re either on the diet or not. That cookie you just ate put you in the “not-on-a-diet” category, so you blew it and now you’ll have to start over again the next day.

The reality is that while you may see your diet as an all or nothing affair, your body doesn’t work (or think) that way. Instead, it tracks how you eat over time, not cookie by cookie, and it gradually adjusts your body fat accordingly. When you try to lose weight quickly, your body fights back to protect you. It wants to make sure you’ll have enough fuel stored up so you can survive what seems to be a sudden shortage.

5. “I lost a few pounds so I deserve to reward myself.”

Your intention is to give yourself encouragement to keep up your hard work. Rewarding yourself periodically will help you maintain the morale you need to stay on the diet.

The reality is that the ability to eat something that you enjoy should be part of your regular diet. A desire for something becomes a craving when it’s perceived to be unavailable. That’s called the scarcity effect. Dieting creates an artificial sense of scarcity because you feel like you can never have what you want. That makes it more likely that you’ll try looking for an excuse to eat something whether you really want it or not. If dieting makes you miserable, and eating is your idea of a reward for putting up with it, that’s a sure sign that the diet isn’t working for you.

The bottom line is that starting a diet feels virtuous and makes you feel good about yourself. It allows you to believe that you can control your animal instincts. But that’s exactly why they fail: when you’re on a diet, you feel pressured to go against your most basic survival instinct, which is to eat what you want, when you want it, as long as the food is available. If it’s not, you’ll want it more and will seek it out. That’s how we survived as foragers. And that’s why we blow off our diets – because they make us feel that the food isn’t available.

So, what’s the alternative? Use your judgment to make reasonable decisions.

You may not trust your judgment, and worry that if you stop dieting, you’ll end up eating everything in sight. The reality is that you have that history because diets make you feel miserable. After a while, you quit because you hate the deprivation, and you may even binge to make up for it.

But when everything is back on the menu and available, you can choose to eat only what you want and only when you want to, because there’s no diet to rebel against. That could save a lot of misery and unwanted calories too, from all those exceptions that end up blowing up your efforts to diet.

And you won’t need any excuses to eat like that.

Should You Be Tracking Food and Exercise?

September 28, 2016

I’m often asked by patients and friends if I recommend keeping a food or activity diary. I have to admit that I’ve always been very ambivalent about this. I know that for people who enjoy tracking and recording things, it can make them more mindful about their choices and can often have a positive impact on their eating.

So why the ambivalence? For one thing, I’m someone who constitutionally dislikes tracking things. I find it to be a burden, and I’m reluctant to recommend anything to others that I wouldn’t do myself. But I do recommend it for those who enjoy keeping diaries, and for those who don’t, I usually suggest they try an app like MyFitnessPal to help make the process easier. However, there’s now some evidence that suggests that using electronic tracking devices to monitor exercise can actually be counterproductive.

A study published this month in the Journal of the American Medical Association compared two groups of volunteers in a study on weight loss. Before they analyzed the data, the researchers were confident that making the job of tracking easier and more accurate bu using the tracker would help people lose more weight. But that’s the opposite of what they found. Participants who used the electronic activity trackers strapped to their upper arm actually lost significantly less weight than those who tracked their activity by posting it at the end of each day on the study’s website.

Why would that be?

I think there are two reasons that this can happen. The first is a well-known effect in social psychology called “moral self-licensing.” This occurs when people will allow themselves to engage in some behavior that they usually try to avoid if they’re also doing something that feels virtuous; for example, having an indulgent dessert after ordering the chicken entrée instead of beef. It also explains why people will eat a lot of cookies from a package that says “no fat” even though, with all the sugar and carbs, those cookies are at least as caloric as the ones with fat.

Moral licensing can affect perceptions too. A study done a few years ago asked people to estimate the calories in a series of unhealthy meals. Half were shown just the meals, and half were shown the same meals with a healthy side dish – like some celery, a small salad, or a piece of fruit. The ones that saw the healthy item estimated the whole meal to have fewer calories than the ones who saw the same unhealthy meals without the extra veggies. So adding the extra food decreased the total calories. Magic!

I think the same thing might be happening with the people in the study. The group using the app may feel more virtuous that they’re collecting all this activity data, which could make them feel entitled to cut themselves some slack with their eating.

The second reason is that knowing that something or someone is monitoring you and watching what you do feels…well, a little creepy. It can make you more self-conscious, and to feel like you’re doing it because you have to for the sake of the performance, not just because you want to. That can make you feel controlled, which is a motivation killer.

Why? Because even when that controlling force is really coming from you, the fact that you feel like you’re being told to do it interferes with a basic need that we all have: self-determination. It’s like when a teenager is tired of hanging out in a messy bedroom and he finally decides on his own that it’s time to clean up. Then his mom pokes her head in the doorway and tells him he should clean up that mess. His response? Probably something along the lines of, “Don’t tell me what to do – it’s my room!”

Wait – didn’t he want to clean up? What’s going on?

It’s all about having a sense of authority over our choices. A study done in France showed that when someone is asking for money, whether the person’s a fund-raiser or a panhandler, they’ll get significantly more money just by adding the following little phrase to the request: “But you are free to accept or refuse.” Well, you might say, of course the person is free to refuse, why would hearing that affect their decision? Because hearing that statement out loud overrides that same admonishing inner voice and allows you to behave more naturally. Without feeling pressured, your natural response might be a bit more generous.

But it’s one thing to reject outside pressure and refuse to do something that you ordinarily would do. What about those who end up doing things that they really don’t want to do, like the emotional eaters I see in my psychotherapy practice? They genuinely want to stop binge eating, but feel they can’t. Why would they repeatedly, and even compulsively, keep doing something that they know they’ll regret?

We’re hard-wired to want autonomy over our own lives. When that need is threatened by feeling controlled, we may act even against our own preferences in order to rebel against that voice that’s pressuring us to do what we know we should do. The result is that people who try to lose weight because they feel they should, may end up doing the opposite of what they want and sometimes even go to the other extreme – just to feel free.

Perhaps giving yourself permission to eat something simply because you want it may actually help you to say no when you don’t, or to say “enough” when you feel it is. That’s what I tell my patients, and it works well for them.

And you might want to try this the next time you want your teen (or teen-equivalent) to do something that needs to get done around the house: “Sweetie, I’d like you to load the dishwasher – but you’re free to do it or not.”

You may be surprised!

Troublemakers in Paradise

September 21, 2015

Our struggle with controlling our behavior has a long history. The first recorded diet long pre-dated Jenny Craig or Weight Watchers; when God told Adam and Eve to avoid eating from the Tree of Knowledge, their freedom to make their own dinner plans was indeed somewhat restricted. Unsurprisingly, they responded the way most people respond to being on a diet: they went to the Tree of Knowledge “…and they did eat.”

There are many views about the purposes of mythology, but one that’s frequently mentioned is that it’s to help us understand human nature, and through that, to teach us universal truths about ourselves. The moral lesson that’s usually drawn from the Eden story is that it’s important to exercise self-control, and that when you give in to temptation, bad things will happen.

But is resisting temptation the real point of the story? Before the snake came along, the only thing Adam and Eve knew about the forbidden fruit was that they would die if they ate it. Meanwhile, they were surrounded by “trees that were pleasing to the eye and good to eat” and they were told to enjoy them all…well, except for that one—that’ll kill you. Seriously, how tempting could that fruit have been?

It seems clear that the Eden story and the concept of forbidden fruit does, in fact, describe a basic characteristic of our nature that has been observed throughout recorded history: that people simply enjoy doing what they’re told to avoid. This human tendency is usually just acknowledged with a sense of wry irony, as if that’s all that needs to be said about it. Instead, let’s examine it more closely: Of course it’s well known that people are drawn to things that are forbidden; but why?

In his book Escape from Freedom, Erich Fromm points out that eating from the Tree of Knowledge in the Eden story became the religious paradigm of transgressive behavior—“original sin” in Christian doctrine. But it also makes a statement about how we respond to control: “From the standpoint of the Church which represented authority, this is essentially sin,” Fromm writes. “From the standpoint of man, however, this is the beginning of human freedom.”

He appears to be suggesting that there is a basic human impulse to violate imposed rules and restrictions in order to assert independence from authority. Eating the forbidden fruit was a defiant act of liberation driven by a basic need to resist control. So there is indeed an important lesson to be learned from this story, but it’s not about temptation; it’s about why we’re motivated to want what’s forbidden. Namely, we’re naturally motivated to resist external control in order to assert our basic human need for autonomy. Maintaining autonomy, then, is an end in itself, rather than a means to achieve some satisfactory outcome; in fact, sometimes the outcome will be unwanted.

The Diet Tax

July 23, 2015

Are diets on their way out? Surveys done over the past twenty years suggest that’s the case. The NPD Group, which monitors trends in eating, reported in 2012 that only 20 percent of adults surveyed said they were on a diet, down from a peak of 31 percent twenty years earlier.

One hopeful way to explain this trend is that perhaps people are finally accepting the fact that no diet offers a quick and easy solution for weight loss and that a more moderate and sustainable approach to eating works best. A recent report from the Centers for Disease Control, however, suggests that’s probably wishful thinking. The report, released in May, shows a continued rise in obesity rates, while the ranks of the moderately overweight remain undiminished. When the top rank keeps growing and the others are stable, it means that each weight class is graduating to the next level.

So why are people giving up on diets? As social beings, we have a hard-wired need for acceptance and we try to comply with the expectations of good citizenship. At the same time, however, we also have a strong instinct for self-determination and freedom from the control of others. These dual needs for belonging and autonomy are both adaptive, but they can conflict with each other. We resolve that conflict by weighing the costs and benefits and arriving at a balanced compromise.

Work, marriage, parenthood, even following the rules of the road when we drive, are all areas of our life that require us to compromise some degree of personal freedom, and we agree to it because we benefit as well. But when we comply with social expectations and find the costs are excessive or the benefits are not forthcoming, we’re likely to feel cheated and stop trying. Apparently, that point has arrived with dieting. Dieters feel they have more requirements for admission than everyone else and they eventually view the pressure to lose weight as a kind of unfair social tax. It’s as if they’re being asked to pay a surcharge on the usual membership dues that everyone pays to be accepted into society and they finally decided that it’s just not worth it.

Why now? One possibility is that while the cultural and social pressure to diet may not have diminished, perhaps the cost of rejecting it has. As the average weight of both men and women increases, there appears to be a parallel shift in attitudes toward attractiveness that may be more accepting of a larger body type. A revealing item in the report of the NPD Group found that over the same period that saw a shift away from dieting, fewer people agreed with the statement that “people who are not overweight look a lot more attractive”—from 55 percent in 1985 to 23 percent in 2012.

That may be a positive indication about our greater acceptance of others, but it doesn’t mean that we’re happier or more accepting of ourselves. Judging from my experience as a psychologist who works with people around issues of self-perception and how it affects the desire to lose weight, we remain very unhappy with our bodies and our eating. As a result, we continue to struggle with ambivalence around feeling pressured to diet and the desire to reject that pressure.

How can we attain a healthy and personally acceptable body weight and shape, without feeling controlled by the diet mentality? The key is to recognize that you are in control—it just doesn’t have to be “control” in a restrictive sense, but in the sense of regulating your behavior, the way a thermostat controls the temperature or a stoplight controls traffic. Your food choices are yours alone and you can learn to trust your decisions.

On a restrictive diet, any question you might have when you’re making a food choice must first pass the test of whether or not it’s allowed. But when your approach to food is self-regulated, everything is on the menu; the only relevant question is whether or not you want it. If the answer is yes, eat it and enjoy it. If not, leave it alone. It will still be available when you really do want it; the world will not run out of chocolate chip cookies.

When your food decisions are guided by personal choice rather than social defiance, you’ll find the weight coming off more easily—and certainly more enjoyably—than dieting.

The Dieter’s Gamble and the Prisoner’s Dilemma

March 4, 2014

In an earlier post I talked about how our innate sense of fair play can make the experience of dieting feel unjust. But what does justice or fairness, which involves preventing or resolving conflict between an individual and others, have to do with an individual’s own internal conflict about dieting? If fairness is a social issue, it should be irrelevant for helping us understand the struggle with emotional eating and self-control.

Or is it? I’ll return to the topic of dieting later, but first let’s explore the evolution of social cooperation for some background to answer this question.

Where do our notions of fairness come from? We’re taught at an early age to wait our turn, not to cheat and to share our toys. It would seem that we need to be educated about these rules so that we don’t act on our childlike impulses to take every selfish advantage that we can and not play well with others.

To a large degree, though, we seem to grasp many of these ideas intuitively. For example, we may learn in driver’s education who has the right of way at a four-way stop sign, but we don’t question why that’s fair; we just know it because it’s obvious that there should be some protocol. And when we learn that it’s a version of first-come-first-served, it seems right. We can instantly grasp that it’s not just unsafe but wrong to jump your turn at the intersection, or to feel angry at someone who does.

I’m also sure you’ve seen very small children who, even though they’re too young to have learned the rules, will instinctively reach out to a crying playmate by offering a toy or sharing a treat. It seems that when we learn rules for getting along in pre-school, it’s more like the driver’s ed class: a formalization and reinforcement of social rules that we already know or can figure out instinctively.

This combination of learned social skills and innate altruism competes with our natural inclination to act in our self-interest. But why are we apparently willing to make any sacrifices for others if the rules are unwritten and unenforceable? And how does a system for social cooperation develop in the first place?

It seems that they’re not entirely unenforceable, at least informally. We struggle with the ongoing tension between taking care of our own needs and setting them aside for the good of the social group that we’re part of. There are times when it’s appropriate to inhibit our self-indulgent impulses, not only for the greater good, but for our own good as well.

I’ve written frequently about our need to maintain a balance between overriding our impulses and letting go of self-restraint. More recently, I’ve come to believe that the tension created by maintaining this internal balance is rooted in and parallels a broader human need to find balance in our interpersonal social interactions. Both conflicts – the individual and social – are similar and are both ultimately driven by self-interest. They require a sense of trust that the sacrifice invested today (in the group or in one’s future self) will result in a greater reward at some later time.

When this conflict of interests between individual needs and group needs is the subject of study, it’s known as the Tragedy of the Commons. This refers to the need for herders to set limits on grazing their own flocks on a common pasture. Although grazing as many as they can would be in their own short-term interest, they limit their flock in order to preserve the resource for the benefit of everyone (including, of course, themselves).

Some degree of self-limiting behavior is seen in all social groups. There are about fifty species of small fish who live off the tiny parasites that they pick off the teeth of larger fish. In the short-term, of course, the larger fish could get an easy meal by simply snapping their jaws shut while the little fish are going about their jobs of cleaning their teeth. But in the longer-term it pays for them to restrain that impulse and benefit instead from this steady symbiotic arrangement. It’s a kind of primitive social contract that nevertheless involves very evolved “human” traits like trust, reciprocity, mutual dependence, self-control, altruism and investment for the future.

Ethologist Konrad Lorenz describes how animals competing for mating opportunities or territory curb their aggression against rivals. Rather than engaging in a fight to the death, such competition is more typically carried out like a ritualized jousting tournament. Why do the animals hold back? Because a rival who survives today can live to be an ally tomorrow, and that may prove useful when competing against other groups. Like Lincoln’s famed “team of rivals,” there are benefits in winning the prize without eliminating the competition.

This kind of strategic restraint has been studied by social psychologists and game theorists using a model of social behavior called The Prisoner’s Dilemma. The name refers to a hypothetical situation in which two partners in crime are arrested for armed robbery, but the police need at least one of them to give up the other in order to have enough evidence for a conviction. Each can choose only one of two moves: COOPERATE and observe the criminal code of silence or DEFECT and implicate the other.

There are four possible outcomes:

- They both cooperate. All the police can do is charge them each with breaking and entering and they’ll both get only a year in jail. That’s “the reward for mutual cooperation” and it’s a fairly good outcome.

- They each defect. Both are charged with the more serious offense and serve two years in jail. Call that “the penalty for mutual defection” which is a fairly bad outcome.

- One defects and goes free, a very good outcome and is therefore called, “the temptation to defect”…

- …while the other cooperates and gets a three-year sentence for the robbery and obstructing justice. The worst outcome, called “the sucker’s payout.”

In the research setup, points are awarded that reflect the relative value of the different outcomes: 0, 1, 2, and 3.

In a one-time competition it’s always best to defect because you have a chance of a big score and you can never do worse than your opponent. But in a real social group, members will interact repeatedly over a long period of time which changes the strategy. If you always defect, others are likely to retaliate later. In studies on interactions in a social group a modified version of the game is played called the Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma, in which the game is replayed repeatedly.

So which strategy works best for the good of all?

Robert Axelrod, a political scientist at the University of Michigan, describes the approach he took to answering this question in his book, The Evolution of Cooperation. Axelrod and his collaborator, biologist William Hamilton, put out a call to game theorists around the world to submit computer programs with what they believed would be the best strategy. The winner is the strategy that has the highest score after going against the others in a round-robin tournament.

In the end, the winning program was a program called Tit for Tat. It’s the most successful strategy for fostering a stable social system and had the simplest and most intuitive rules of all. Simply put, it’s “I’ll scratch your back if you scratch mine.” But there’s also an implied corollary to this conditional offer: “and if you don’t, you can forget about me tending to your itchy back next time!” The rules for this strategy are simple: you begin by cooperating on your first move, then you just copy your opponent’s moves after that.

Here’s a real world example of how this strategy can be used. An investor is asked during a business meeting to write a proposal for a deal. He’s the best qualified person in the group to do it, but he thinks it would be considerate of him to pass a draft around so others can have an opportunity to comment on it. [PLAYER A: COOPERATE?]

But then he considers the possibility that it would just open the door for someone who might begrudge him the privilege of writing the proposal to criticize his work or shame him by making a disparaging comment [PLAYER B: DEFECT?]. He never said during the meeting that he would pass it around, so why risk it? [A: DEFECT?]

He finally concludes, “If someone else wants to act like a jerk, let him! I’m not going to assume there were any jerks in that meeting until one declares himself.” [A: COOPERATE] So he sends it around and gets positive feedback from everyone. [B: COOPERATE] Both sides (he and his potential rivals in the group) receive the “cooperators’ reward” because they’re now a more cohesive team, which will help in negotiating this and any future deal.

The Tit for Tat strategy is successful because it strikes the right balance between being generous and being selfish. It’s friendly, but it’s no pushover. When more forgiving programs were run, the hypothetical group using the strategy was exploited. Less generous programs that anticipated selfish behavior and defected on the first move were punished – even if the rest of the moves followed Tit for Tat.

This is the basis for reciprocal altruism. It’s altruistic because we suspend our own needs for someone else’s benefit. It’s reciprocal because that person will do the same or else his privileges that come with group membership will be suspended until he cooperates.

Now we can turn back to the question of how this relates to an individual’s conflict around self-control. When a dieter, for example, feels the impulse to indulge in something that’s not allowed on her diet but restrains herself in order to lose weight, how does she expect to benefit from this sacrifice?

It depends on the basis of her motivation to diet. She may view the diet as something that really comes from her and when she sticks to the rules, she genuinely feels that she’s doing exactly what she wants. This does happen sometimes and it’s likely to bode well for the success of her dieting efforts.

Now consider someone who is on a diet because she feels pressured somehow. Perhaps it’s the cultural pressure to be thin or she’s getting ready for the summer or a beach vacation. Even though her conflict is going on in her own head, if she’s trying to comply with perceived social pressure, the Prisoner’s Dilemma is likely to play a role in her diet strategy.

Her opening move in the game was COOPERATE. Her expectation was that she will, at some point, experience a return on her investment, like greater social acceptance, success, or attention, because she will lose weight. At first, it’s likely to go well as long as the scale keeps showing steady progress, or the compliments keep coming, or the clothes that she hasn’t been able to wear in a while begin to fit again.

But once those reinforcements stop – and eventually they do – she’ll begin to wonder why she’s doing this. The fact that others are able to maintain their weight without dieting will become more irritating. Most importantly, if the expected improvement in social acceptance and career or relationship success has not come through, she’ll be left with nothing but the deprivation, food rules and low-calorie desserts. It’s the ultimate sucker’s payout.

This is the kind of experience that puts the “emotion” in emotional eating. It’s a sense of betrayal and false promises that generates anger and a defiant abandonment of self-restraint. Her emotional eating, then, is the Tit for Tat strategy to play the DEFECT move because she feels betrayed and angry that her COOPERATE move was not reciprocated. It’s the right strategy to play in the iterated prisoner’s dilemma: cooperate first and continue to do so as long as the other guy does as well, but respond in kind if he defects.

There are two takeaways: First, if your decision to diet is truly coming from you, whether to reduce health risks, increase self-esteem, or any intrinsic motive, you’ll likely reach your goal and will feel good about the process. But doing it just to play the social cooperation game is a setup for feeling betrayed.

Second, if the emotions that you experience when you break the rules of the diet feel like resentment or angry defiance, then it’s probably a sign that you’re feeling cheated. But it’s like a shell game of Three-card Monte or Find the Lady: once you figure out that it’s a scam, you’re smart enough not to fall for the hype.

Cause and Effect in the Here and Now

February 11, 2014

This has been a terrible winter by any measure, but one of the most frightening and dangerous effects has been on highway travel. Snowstorms have caused several multi-vehicle pileups, some fatal. The worst one (so far; it’s only February) happened in Wisconsin where most reports counted at least 50 cars that were involved in the calamity, and others said as many as 90. Whatever the number, you can see in the video that it seemed like an unending chain reaction. You can also see what may have been some of the immediate causes of the pileup: poor visibility from the snowstorm, slick roads, cars too close together, driving too fast for conditions – all adding up to the inevitable outcome.

When people come to me for help to stop unwanted behavior, like emotional eating, binge drinking, or other out-of-control behavior, they’ll often say, “I want to know why it happens.” It’s a very reasonable request. It gives people real satisfaction to understand the root of a problem. It can provide a sense of perspective or a useful insight, and those reasons may make it worth discussing. But I also try to explain that whatever the remote cause might have been, it’s mostly irrelevant in helping them to stop the behavior.

Unwanted behavior is the result of a series of events and experiences that lead up to the present. The original cause may have been pretty benign, but small causes can build on each other until they develop into very large effects. Finding the original reason that started this chain reaction doesn’t tell us how to keep the process from continuing. Recognizing old experiences and patterns of thought that may have led the behavior is essential in preventing the same problem from occurring again in the future. But for any change to happen now, the focus needs to be on the present, not the past.

I was discussing this with someone recently and while I was searching for an analogy to help me explain it, the image of the highway pileup came to me. I asked her what she thinks the first responders should do when they arrive at the scene. Should they start by investigating the cause while cars are crashing around them? Should they find the first guy who was going too fast or the one following too closely behind? Of course not. Those people may be long gone and are probably even oblivious to the mayhem they caused. The first thing to do is to try to prevent the very next crash from occurring and get everyone out of harm’s way.

After the responders are able to safely stop the traffic upstream and after attending to the injured and clearing the wreckage, it would make sense to go back and investigate the causes and take preventive measures to keep this from happening again. Some circumstances can’t be avoided, like the weather, but other causes can be addressed in order to minimize the likelihood and consequences of similar highway disasters occurring in the future.

The same applies to unwanted behavior. The first priority is to find ways to stop the behavior and prevent further damage. That means identifying and challenging the thoughts, beliefs and distortions that lead to the emotional reactions that the behavior is meant to cope with. It’s like The House that Jack Built. After that, you’ll have the time and perspective to do a useful postmortem so you can identify the sources of the problem and do what you can to make sure it doesn’t recur.

The video may be harrowing to watch, but if you’re struggling to overcome emotional eating or any unwanted behavior and you’re spending time focusing on the past or looking for others to blame for it, think about the image of those cars racing headlong toward the disaster, spinning out of control, and crashing into each other like bumper cars from hell. Then think about what you would do as a first responder.

Dieting and the Scarcity Heuristic

December 18, 2013

There is a concept in psychology and behavioral economics known as the scarcity heuristic. It simply means that when there is something that we want but are afraid we can’t have it, we want it even more. But scarcity affects more than how much we want something; it also affects how we behave when we find it. And that has important implications for our patterns of consumption, both economic and gastronomic.

It’s now the period between Thanksgiving and Christmas, after Black Friday and Cyber Monday. It’s a time when retailers try to create the impression that you have a unique but brief opportunity to buy their products on sale. But you have to do it now, because soon they’ll be gone and you won’t have this chance again.

The reality, of course, is that manufacturers and retailers know well in advance how many units of each product need to be produced and there will be no shortage. But by making you believe that demand is greater than supply, they create a sense of desperation to buy now because if you wait, you’ll lose out. This may be great for the economy, but as a psychologist I’m more interested in how this might affect us in other ways that may be less benign; like how we think about food and why we overeat.

Biologists who study foraging behavior have found that when animals search for food as a group they find it faster than those that forage alone. There was one downside to doing it this way, though: once they found a patch of food, each individual in the group had to compete with the others so they don’t get left out and go hungry. This created a competitive scramble that probably looked a lot like the 6am scrum at the JCPenney door buster sale. It seems we’re just hardwired to take advantage of holiday sales because as foragers it was a strategy for survival.

I think this can help us understand other behaviors as well, especially something like emotional eating, which is my area of specialty as a psychologist. Even though in most of the world today there’s no actual food scarcity, we still feel desperate when we believe that we won’t get our fair share. Have you ever walked into the break room at work and found that someone brought in a plate of cookies? Even if you’re not really in the mood for a cookie just then, you wonder if there’ll be anything left later when you might want one. So you take it while you have the chance.

A more serious version of this, however, involves chronic restrictive dieting. Regardless of how much food is available, if you’re a strict dieter, you’ll always feels like there’s a food scarcity. The knowledge that you can’t – or rather, the feeling that you shouldn’t eat what you like can make you feel constantly deprived. Yet you keep trying your best to stay on track and resist. Most of the time you’ll succeed, but there’s only one way to be perfect and countless ways not to – especially at this time of year, when the opportunities to eat seem endless.

And when you, as a dieter, do let down your guard and allow yourself the chance to have a “forbidden” food, it’s not enough to just have some. Because once you give in, the gates are open and the urge to keep eating is hard to resist, just like that hungry forager who finally finds a patch of food. He would say, “I better eat while I can, because if I wait it will be gone and who knows when I’ll have the chance again!” The dieter says, “I better eat while I can, because once I go back on my diet I’ll stay on it forever, and who knows when I’ll have the chance again!”

I tell my patients that the only question to ask yourself when you’re making a decision to eat is simply, Do I want this? If you’re on a diet you can’t answer that question honestly, because you’re always supposed to say no. But if you allow yourself to eat what you like, then an honest answer to the question, Do I want this? will let you to enjoy eating without overindulging. Because if the answer is yes, you eat; if the answer is no, you move on. There will always be another chance when you really do want it.

You may enjoy the experience of foraging for toys among a herd of bargain hunters. But no one who struggles with emotional eating enjoys the guilt and shame that accompanies every encounter with food. The conflict that occurs when the diet mentality meets an eating opportunity can be avoided when all foods are good, and permitted, and back on the menu. Then an enjoyable meal without anxiety will no longer be a scarce resource.